SEPHARDI AND MIZRACHI CUISINE

Regions with a warm climate have provided Sephardi and Mizrachi Jews with an abundance of fresh fruit and vegetables. Among the vital ingredients used in their cuisines are: olive oil, vegetables (such as eggplants, zucchinis, artichokes, fresh fava beans, peppers or tomatoes), lamb, chicken, sea fish, rice, chickpeas, lentils, yoghurt and dates.

Sephardic and Mizrachi cuisines are aromatic thanks to the use of spices (turmeric, cinnamon, cumin, coriander, cardamon, caraway, ginger), fresh and dried herbs (cilantro, mint, dill, hyssop, fenugreek), and scented waters (rose, orange). Due to the vast territory they used to cover and its complex history, Sephardi and Mizrachi cuisines are very diverse—they are inspired by culinary traditions in the Middle East, North Africa and even the Far East. .

Persian tahchin. Rice, saffron nad agg dish with eggplant.

Photo: Armando Rafael / Jewish Food Society, New York

Sephardi Jews

Since Late Antiquity, Sephardi Jews (Heb., "Sefarad" – Spain) settled on the Iberian Peninsula and resided there under Muslim rule. After the Reconquista in the late 15th century, they were expelled from the Peninsula by Christian rulers of Spain and Portugal, and they began to settle in Western Europe (especially the Low Countries, Italy, England)s. Other Sephardim moved eastward to the Balkans, the Mediterranean basin, and North Africa in areas that were then part of the Ottoman Empire. Sephardim usually spoke Ladino, a fusion of old Romance languages spoken on the Iberian Peninsula, Hebrew and Aramaic. They retained close links with Mediterranean and Middle Eastern culture.

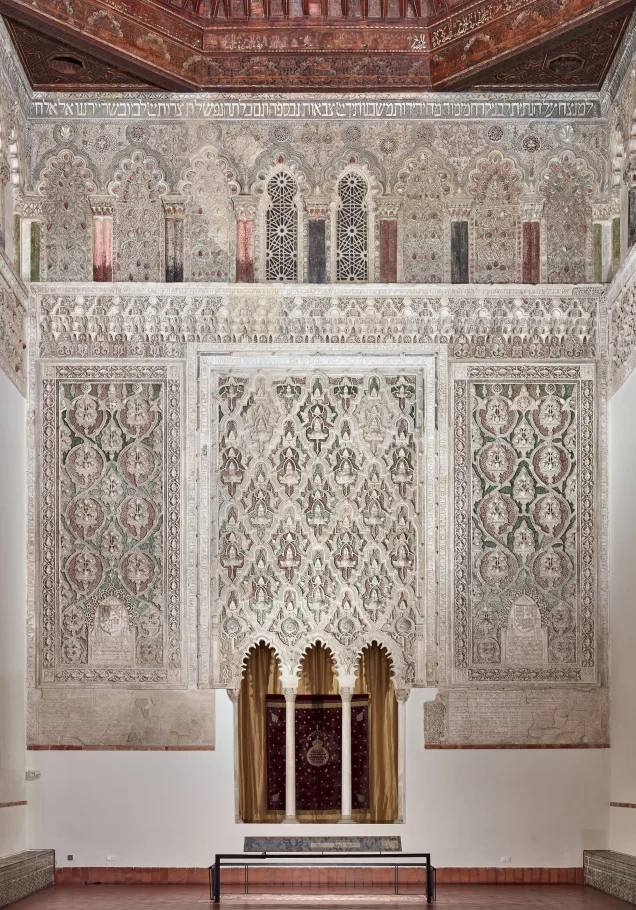

Eastern wall in El Tránsito synagogue in Toledo

The synagogue was built between 1356 and 1357 and was converted into a church after the expulsion of Jews from Spain. Currently, it houses the Museo Sefardí. Photo: David Blázquez, 2019.

Archivo del Museo Sefardí, Toledo

Mizrachi Jews

Mizrachi Jews (Heb. "Mizrachi" – eastern) have lived in the Middle East, North Africa and Central Asia since antiquity. When Sephardim arrived from Spain, Mizrachim adopted some of their customs and combined them with the Oriental tradition. There were groups, however, such as Jews from Yemen (Heb. "Teymanim") who retained separate customs and traditions.

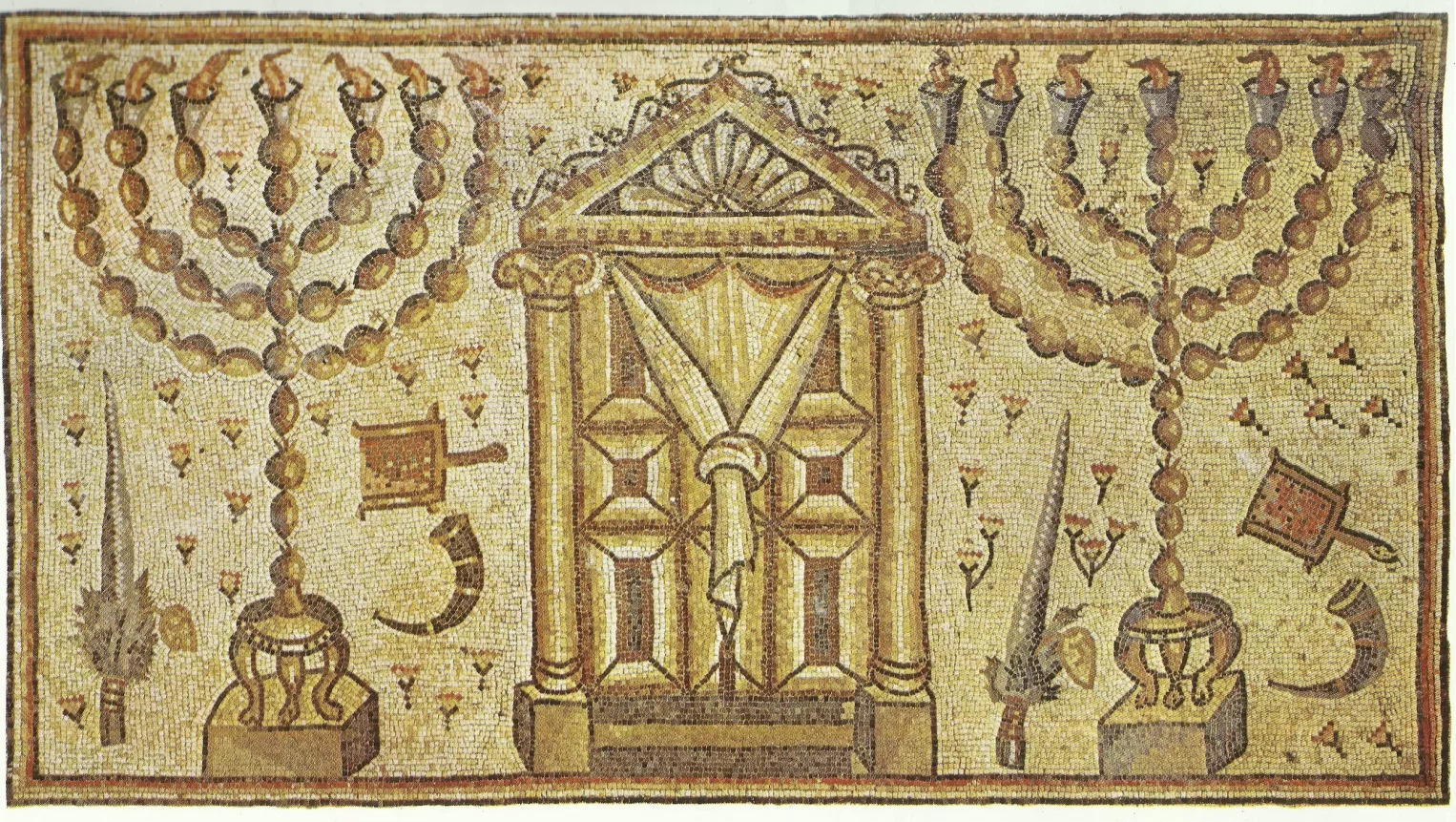

"The Ark of the Convenant and the Temple utensils"

Fragment of a floor mosaic from a synagogue in Hammath near Tiberias, 4th c.

A photo from: Gabrielle sed Rajna, Ancient Jewish Art. East and West, 1985

The ancient roots of Mizrachi Jews

In Antiquity and in the early Middle Ages, Jews resided in the Middle East (South-West Asia and North Africa) where they remained under the influence of the great empires: Persian, Hellenistic, Roman and Byzantine. Their traditions changed significantly in medieval times, when the entire region was dominated by Islamic culture.

One of the oldest Eastern Jewish communities which retained their individual tradition and customs to this day are the Jews of Yemen. Yemeni Jewish dishes are very spicy, mainly thanks to z’houg—a paste made of chilli peppers, cilantro and garlic.

One of the oldest Eastern Jewish communities which retained their individual tradition and customs to this day are the Jews of Yemen. Yemeni Jewish dishes are very spicy, mainly thanks to z’houg—a paste made of chilli peppers, cilantro and garlic.

Earthenware: jar, plate and bowl

Egypt, 8th-11th cc. discovered in Cesarea.

The Israel Museum, Jerusalem

In the Caliphate - flavours from around the world

From the 7th century onwards, Jews in the Middle East were subjected to the growing influence of the Islamic culture. From the 8th to the 11th century, Baghdad was the centre of the Arab world. Trade flourished throughout the region. Local cuisine was a mixture of local traditions as well as Far and Middle Eastern influences. People consumed rice and eggplants from India, spinach from Nepal, melons from Egypt, figs from Constantinople, pomegranates from Persia, and watermelons from Africa. Food was seasoned with garlic, cumin, coriander, ginger, saffron, sumac, orange or rose water, raisins and pine nuts. Jews engaged in the trade of olive oil, sesame, fish, dried fruit, nuts, honey and spices.

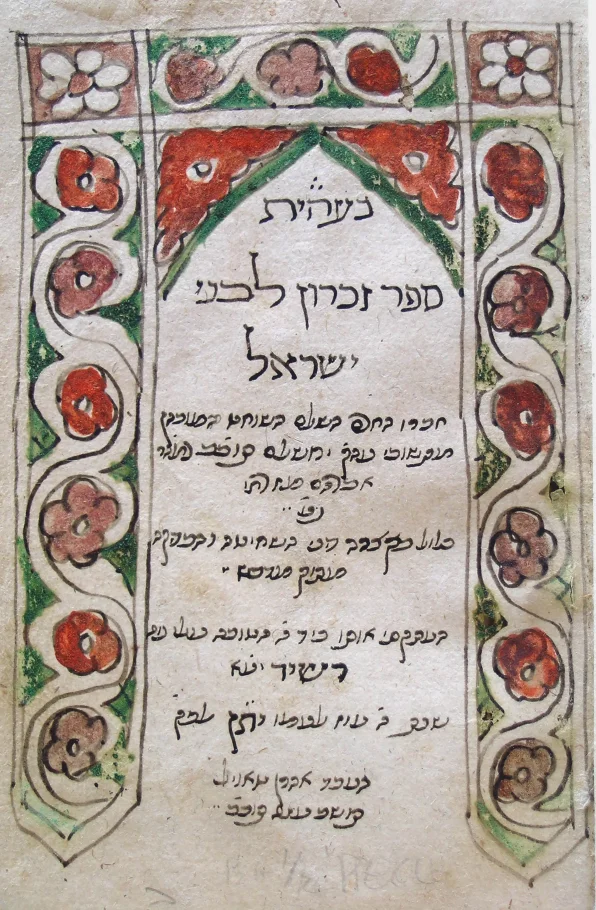

Avraham ben Baruch Mizrachi, "Zikaron le-Benei Yisrael"

Manuscript with rules of ritual slaughter. Egypt, 1700.

Gross Family Collection, Tel Aviv

Santa María la Blanca synagogue in Toledo

The synagogue was erected in the 12th century in the Mudéjar style which combined Muslim and Gothic art. At the beginning of the 14th c. it was changed to a church. Photo: before 1938.

Jewish Historical Institute, Warsaw

In Muslim and Christian Spain

The times of the Emirate and the Cordoba Caliphate (8th-11th centuries) were the “golden era” for the Jews on the Iberian Peninsula. The surviving cook books from that period testify to a refined diet. Recipes are full of dietary recommendations. This is not surprising since Jews at that time developed advanced medical knowledge by adapting Greek and Islamic medicine. In the wake of the Reconquista in the 12th-14th centuries, Jews gradually found themselves under Christian rule. They often served as a link between the Arab and Christian worlds and also contributed to the exchange of culinary traditions. Marzipan is one example: consumed by the Jews mainly during Passover and Purim. Jews also popularised eggplants and artichokes in Europe.

Preparing for Pesach

Illustration in the so-called "Golden Haggadah" produced in 15th century Spain.

British Library, London

Migrations of Sephardi Jews and of their culinary traditions

In the 14th-15th centuries the situation of Jews in Christian Spain deteriorated—they were persecuted by Church authorities and forced to convert. Jews who converted to Christianity but continued to secretly practice Judaism were called Marranos (spanish."pigs"). They were persecuted as heretics and tested by being forced to consume treif foods such as pork. Ultimately, towards the end of the 15th century, the kings of Spain and Portugal issued decrees ordering Jews to leave the Iberian Peninsula. Following the expulsion, Sephardi Jews settled in other European states such as the Low Countries and in Italy, while some resettled in the Middle East or the Balkans.

Portuguese Jewish family eating Seder dinner

Copperplate engraving by Bernard Picart, Amsterdam-Paris, 1724

Gross Family Collection, Tel Aviv

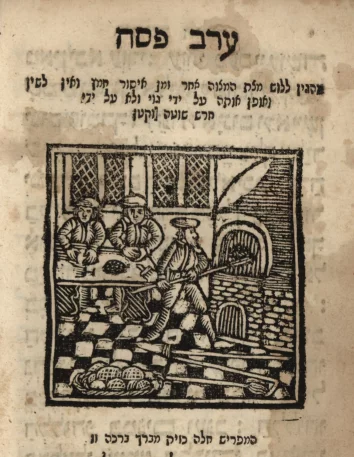

Baking matzo

Illustration in "Minhagim" – a collection of religious law dedicated to the annual cycle, published for Sephardic Jews in Amsterdam (with some notes in Spanish), publ. Leib Zussmensch, Amsterdam, 1786

Gross Family Collection, Tel Aviv

In the Ottoman Empire

Between the 16th and 19th centuries, the Ottoman Empire was the main centre of Sephardi culture. Sephardic Jews dominated most of the existing Jewish communities, and some of the cities such as Thessaloniki, Smyrna (Izmir) or Rhodes became vibrant Sephardi cultural centres. They never forgot about the Spanish culinary tradition, but they combined it with elements of Turkish cuisine. Kebab, pilaf (a dish made of rice, vegetables and meat), stuffed vegetables and baklava were introduced into the Sephardi menu.

SCROLL or CLICK&HOLD

to go on