LOCALITY AND CUSTOM

Jewish cuisine is extremely diverse—it evolved tremendously over the past 3,000 years in many corners of the globe. Available products and various climates forced Jews to adjust their dishes to local conditions. Most often, Jews were inspired by the foods around them and adapted the recipes according to the rules of kashrut. By migrating, they played an important role in popularising certain products and dishes in the Jewish and non-Jewish world.

Diaspora

The oldest Jewish communities in the diaspora date back to Antiquity— in ancient Persia, Babylonia, Egypt, Greece and the Roman Empire. Mass dispersion of the Jewish people began after the Roman conquest of Palestine, the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE and the subsequent change of the name Jerusalem into Aelia Capitolina in 135 CE. From then onwards, Jews began to settle in the Mediterranean basin and in the Middle East. With time, they split into separate ethno-cultural groups, mainly Sephardim, Ashkenazim and Mizrachi Jews.

WHAT EXACTLY IS JEWISH CUISINE?

Leah Koenig, a New York-based writer and author of cookbooks, talks about the diversity of Jewish cuisine and how kosher principles are applied to local products and climates.

Differences

Jews in the diaspora, subjected to different surroundings and climates, developed their own local flavors, customs and aesthetics. Their synagogues were built in various architectural styles, and their ritual objects boasted varied ornamentation and iconographic motifs.

Regional differences were also evident in some of customs stemming from interpretations of religious laws. For example, the Ashkenazi tradition does not allow Jews to eat legumes (aside from grains), corn and rice (the so-called "kitniyot") during Passover, whereas the Sephardim generally do not observe such a prohibition.

Regional differences were also evident in some of customs stemming from interpretations of religious laws. For example, the Ashkenazi tradition does not allow Jews to eat legumes (aside from grains), corn and rice (the so-called "kitniyot") during Passover, whereas the Sephardim generally do not observe such a prohibition.

Hanukkiyah, silver, Poland, 18th c.

Ashkenazi synagogues and ritual objects were often decorated with symbolic images of animals associated with the Torah, God and Creation. These images were influenced by Gothic, Baroque and Classical European styles.

POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews

Hanukkiyah, Morocco, 18th c.

Mizrahi and Sephardi synagogues and ritual objects were influenced by Islamic art in which abstract ornamentation dominated and figurative elements were scarce.

Gross Family Collection, Tel Aviv

View 3D

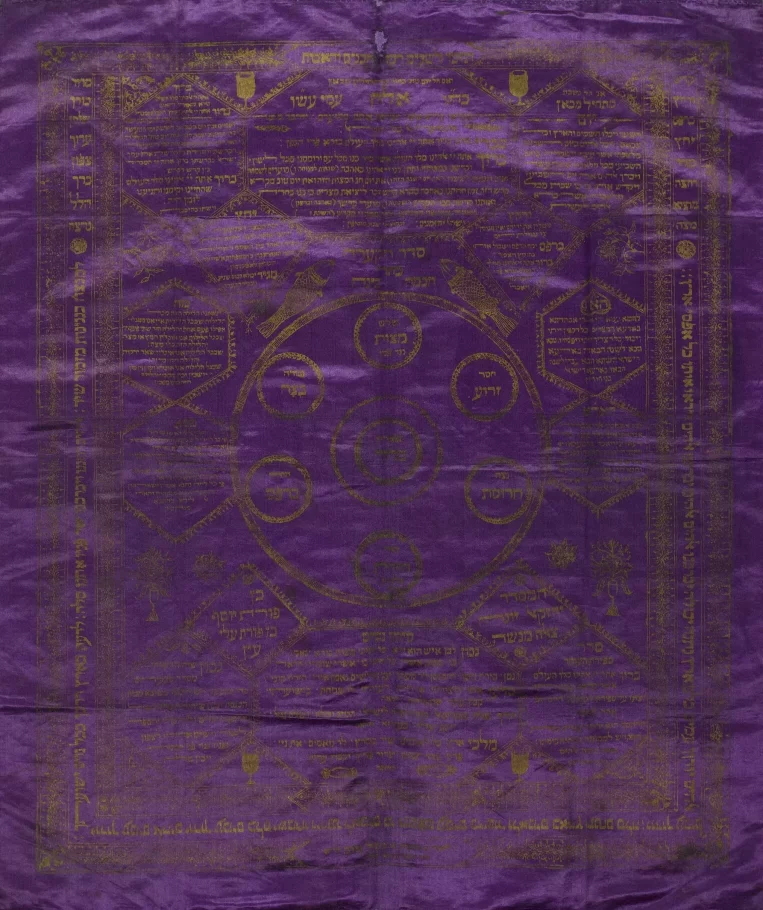

Cover for the seder plate, Iraq, c. 1920

In the Sepharadi tradition, due to the hot climate, seder plates had no markings on them, but instead were covered with a cloth with the names of dishes embroidered on it.

Gross Family Collection, Tel Aviv

Seder plate, Poland, 18th c.

In the Ashkenazi custom, each dish had its own assigned place on the seder plate.

Old Synagogue / Museum of Krakow

SCROLL or CLICK&HOLD

to go on